A sociological review of IPV provides a new perspective on gendered relationships to violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse. The majority of media reports and scholarly research frames IPV along clear gender lines, where men are the abusers and women are the victims. However, IPV can be committed by both men and women and occurs in non-heterosexual relationships.

Research on IPV from the United States (as well as developed countries like the UK and Australia) that focuses on female perpetrators in heterosexual relationships raises several questions.

- Do women and men abuse each other emotionally and physically at similar rates?

- While IPV against women is a major public health concern, is abuse of men by women also a major social problem?

- Should we view physical violence committed by women the same way that we view violence by men?

- How are men’s experiences of IPV both similar and different from those of women?

- How does gender play a role in men’s internal and social experiences of IPV?

Norms on masculinity and men’s role in the family cause men abused in heterosexual relationships to face unique psychological and social challenges. However, there is currently not enough evidence to support the claim that IPV against men in heterosexual relationships is a public health concern of the same scale as IPV against women.

Emotional and Physical Abuse

Emotional abuse is defined as “any nonphysical behavior or attitude that is designed to control, subdue, punish, or isolate another person through the use of humiliation or fear,” but can include physical behaviors that result in psychological, social, and economic costs, such as throwing objects and shaking a fist at the partner.

Emotional abuse can be categorized into six components:

- verbal attacks, including ridicule, verbal harassment, and name calling

- social and financial isolation

- jealousy and possessiveness

- verbal threats of harm

- threats of abandonment

- damage to property

Physical abuse includes acts such as “shoving, slapping, punching, kicking, choking, throwing, scalding, cutting, smothering, or biting.” Some researchers also include sexual coercion in emotional abuse, because the victims are made to feel ashamed and afraid. Acts that do not seem aggressive can be examples of IPV, such as cuddling or any “unwanted touching and invasions of personal space.”

Prevalence of IPV: Gendered Differences

Some of the most prominent results of IPV studies find that women are more likely to be severely injured by their male partners during instances of physical aggression, women reported experiencing more isolation and property damage, and men experience more psychological aggression and abuse. More women report experiencing high rates of physical aggression than men. It’s also important to note that women report higher rates of sexual abuse than men. These findings seem to suggest that women abusing their male partners is a major social problem. However, there are many potential reporting biases to these results.

Theories, Explaining the Data, and Reporting Bias

Social and institutional forces explain why men’s experiences of emotional and physical abuse have increased while women’s risk of experiencing IPV have decreased. Rates of IPV against women have declined as a result of increased resources for female victims of IPV, increased law enforcement awareness of and action against IPV, as well as feminism’s empowerment of women. One abusive wife interviewed in an academic study hints at this empowerment when she says, “I did what every other woman in my place would have done. I was strict, and I am proud of it and acted like any other responsible wife and mother.”

Micro-resource conflict theory also explains men’s increased risk of emotional and physical abuse, because changing gender roles and more equal access to resources have led to more competition between men and women over scarce resources like education. Therefore, abusive behavior may be a manifestation of some women’s attempt to even the playing field.

Scholars also look for explanations of higher reported psychological victimization of men, such as the fact that relational aggression is a more socially acceptable behavior for women than physical violence. Women may fear physical and sexual retaliation if they use violence in part because they perceive men as inherently physically and sexually threatening. Nonlethal violence can also be seen as a less effective tool of control against men because men tend to express little overt concern over assaults against themselves.

Feminist theorists raise strong objections against findings that women and men physically abuse their partners at similar rates and against theories which frame IPV as gender symmetric. Feminist-structural theory on domestic violence views domestic violence as a manifestation of status and power differentials of gender. Domestic violence is a means to dominate women by using coercion and control to maintain the patriarchal oppression of women, based on masculine gender norms of establishing mastery, supremacy, and authority.

In addition, men and women have different views on violence which may lead to reporting bias on use of violence. Men’s tendency to view violence against women as socially acceptable, due to gender power imbalances, makes them more likely to dismiss and minimize their violence against women and/or blame them. In contrast, women readily admit to their use of violence because they are socialized to view abuse as a violation of their prescribed gender role.

Women who experience both violence and emotional abuse may dismiss the latter because they perceive physical abuse from their partner as the greater threat, fail to identify emotional abuse, or only report violence because it is the most visible form of abuse. Women underreporting emotional abuse would explain why men report higher rates for some forms of emotional abuse. The mental and physical consequences of IPV may also be more significant and lasting for women. Studies that report on gender prevalence of IPV also do not account for factors such as motivation for violence and physical and psychological consequences. Men’s primary motivation for using violence is jealousy, the need to control, and intimidation. In contrast, women use violence primarily to defend themselves and/or their children, to retaliate for previous violence and get their partner’s attention.

Not distinguishing between men’s and women’s use of violence holds women to a male standard of violence and assumes that they have the social experiences of a man.

Scholars who study men’s experiences of IPV criticize the argument that women primarily use violence against male partners for self-defense. For instance, some women who initiate physical abuse justify their violence by using self-defense rhetoric and suggest that men cannot be trusted not to act violently.

The argument that women primarily use violence for self-defense is based on two beliefs:

- men are more aggressive and violent

- men are stronger, tougher, less vulnerable and able to cause greater physical harm, due to socialized violence

Scholars address the perception that men pose a greater physical threat and sustain less severe injuries than women because they are stronger and larger. Weapons can serve as “equalizers” for women, enabling them to inflict lethal injuries despite their size. Men sometimes do not retaliate or even defend themselves. Psychological abuse and control can make men think that they deserve the abuse, and they may fear reprisal and escalation which are likely to happen if they defend themselves.

Chivalric masculinity, in contrast to hegemonic masculinity which encourages violence against women, dictates that ‘real men’ never hit women, even in self-defense.

Therefore, some women exploit the well-known issue of violence against women to justify committing abuse using self-defense rhetoric, and greater size and strength do not protect men from being subjected to IPV or sustaining injuries from women.

Psychological and Social Challenges to Masculinity

Scholars studying the experiences of men abused by their women partners found multiple similarities to the experiences of abused women, including acceptance of abuse and blame, progression of abuse, low self-esteem, isolation from friends and family, and reasons for not leaving the relationship. While abused women have to face the social structures that are intended to disempower and subordinate women, abused men need to maintain their internal and social masculine identity and struggle against structures that marginalize ‘feminine’ men.

Victimization is seen as feminine so that any man who is victimized is emasculated in others’ eyes and his own. This leads to the struggle to maintain masculine identity both internally and externally.

Scholars find that abused men use a variety of tactics such as minimizing the IPV and reinterpreting it as a masculine experience. One man interviewed in an academic study reframes his experience of abuse as fortifying by saying that “if it doesn’t kill you, it can only make you stronger.”

In order to reconcile their experiences and others’ image of them, abused men attempt to maintain face by exhibiting disregard for the abuse they experienced or by laughing it off, particularly in front of other men. Many men refuse to identify only as victims of violence by women, instead emphasizing social stigma and how they protected their family members and children. As a result of attempting to conceal their victimization in favor of maintaining their masculinity, men often avoid asking for help, showing fear, and talking to their peers about their abuse.

Biased Institutions

Because of the stigma around men as victims and the dominant narrative of IPV where the man is the abuser and the woman the victim, it is difficult for men who seek help to gain access to resources that are designed for female victims. This is a result of biases held by institutions such as the police, domestic violence shelters, and the courts, which have also been documented to be biased against female victims of IPV.

Many men whose partners had abused them reported being arrested and placed in jail even though there was clear evidence that the woman had carried out the abuse. Others recounted disbelief from both police officers and crisis workers. The justice system similarly dismissed these men’s claims of IPV, and one researcher found that among the abused men he interviewed who had children, none received custody from the courts. Institutional biases against men often contribute to them remaining in the abusive relationships. Abusive women sometimes take advantage of those biases to portray the men as the abusers by threatening to call the police or shelters.

Looking Forward

The purpose of this sociological overview is not to minimize IPV against women by their male partners or to claim that IPV against women and men are social and public health problems of equal magnitude. Instead, further research is needed to make definitive conclusions about the gendered forms of IPV in heterosexual relationships.

By focusing on men who experience abuse in heterosexual relationships, we can identify some of the biases that stigmatize and marginalize people who face abuse but do not conform to the dominant narrative on IPV, such as those in non-heterosexual relationships. Focusing on men’s internal and external experiences of IPV shows that norms of masculinity lead abused men to face different psychological and social challenges than abused women, which can inform what resources better serve IPV victims.

Gender roles define the social relationship between male and female bodies, and create the dominant narrative that only men are dangerous and abusive and only women are vulnerable and victims. There is certainly truth to this narrative, as women are more vulnerable to sexual abuse and violence, but people from an oppressed group are also capable of abuse.

Greater awareness of the specific experiences of male victims in heterosexual relationships complicates the dominant narrative on IPV and helps decrease the stigma faced by victims who do not fit within this narrative, including people in non-heterosexual relationships.

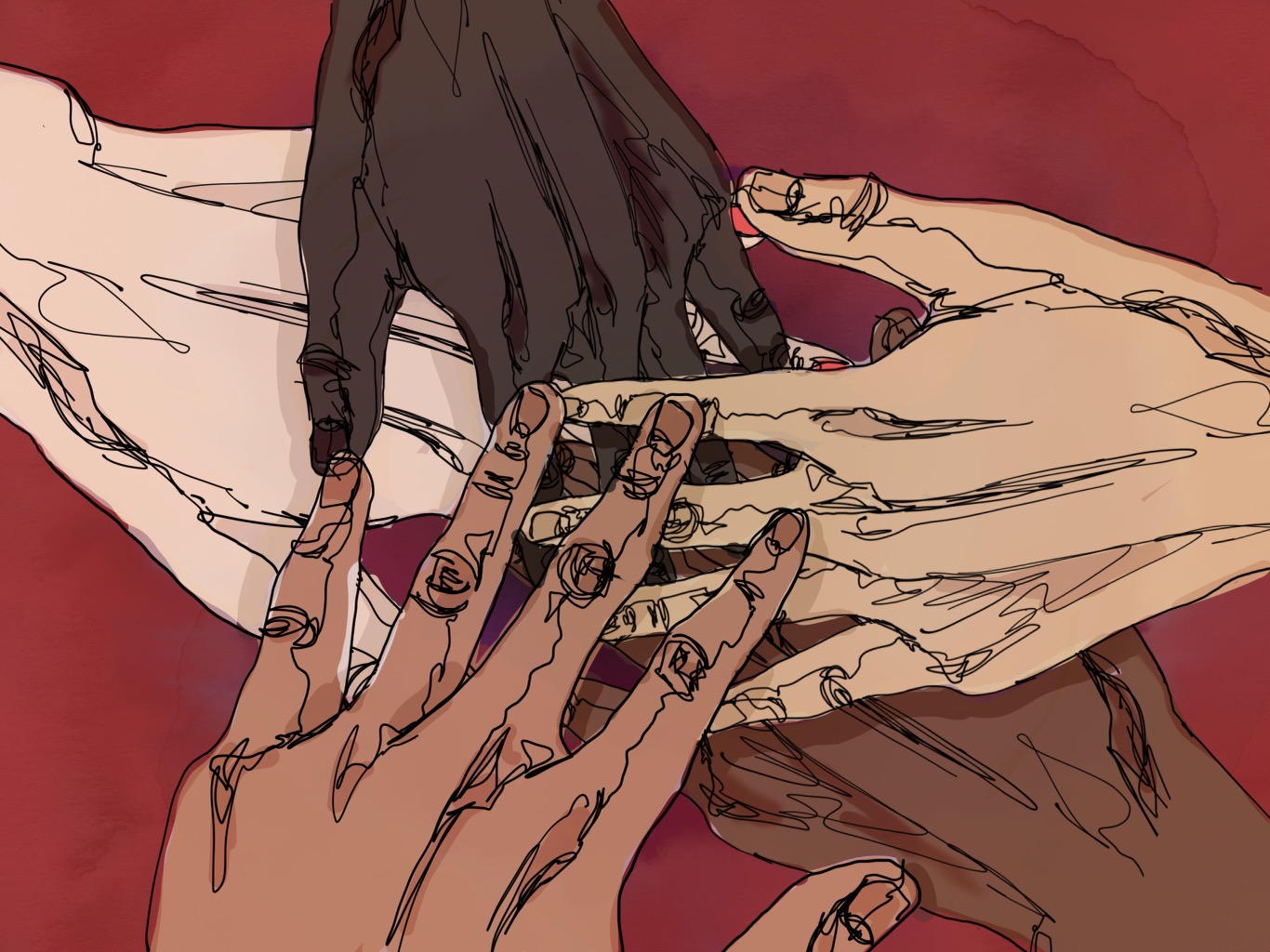

Illustration: Diane Lin is an illustrator and art editor for F-Word magazine. She is a senior majoring in Economics and minoring in Political Science in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania.